Contributing physicians in this story

A concussion is a brain injury, and regardless of whether it is mild, moderate, or severe, it has the potential of long-term consequences. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reports that mild traumatic brain injuries (mTBI), also called concussions, account for nearly 75% of all traumatic brain injuries (TBI). Researchers define a concussion as a transient change of brain function caused by a biomechanical force to the brain after a head injury. During a concussion, brain cells or neuronal axons pull, stretch, tear, and twist, damaging the brain’s electrical chemical pathways. Often, the results are a decrease in brain cell activity and reduction in blood flow within the brain, which can lead to temporary or permanent neurological signs and symptoms (Box 1).

Adults aged 65 and older and children under 14 years old lead the demographics of age-related falls that result in a concussion while motor vehicle accidents are the third leading cause of TBI among all age groups. Concussions are more frequent in teenagers, young adults, males, and people who are engaged in high-impact, physical activities, such as a contact sport. Since sports-related concussions are the leading cause of mTBI, all 50 states address concussion management in school athletics by using return-to-play protocols to protect athletes. The question is then, when can an athlete safely return to sports?

After a head injury

After a head injury

Following a concussion, patients can experience a number of clinical symptoms, such as headaches, dizziness, depression, memory loss, confusion, blurred vision, and balance problems (Box 2). These symptoms can occur with or without loss of consciousness. Some physicians use post-concussion syndrome to describe a range of residual symptoms that persist despite a lack of evidence of brain abnormalities on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computerized tomography (CT) scans. While traditional imaging modalities—such as CT, MRI, position emission tomography (PET) scan, and single-photon emission computerized tomography (SPECT) scans—provide information on brain anatomy, metabolism, energy consumption, and blood flow, they do not provide information on the functional brain or help diagnose concussions. More specifically, these imaging modalities do not allow us to quantify how the underlying brain networks are performing, such as memory, attention, pain, or depression. Other functional assessment methods, including clinical assessment and neurocognitive tools, reveal only clinical effects and symptoms.

How your brain works

The brain contains a complex cellular network of around 100 billion neurons with each neuron connected to around 10,000 neighboring neurons. Neurons “speak” to each other using special chemicals called neurotransmitters. The messages from neuron to neuron flow through electrochemical signals. The signal from 1 neuron is miniscule and not detectable; however, when there are coordinated electrical pulses from groups of neurons, a detectable brainwave is produced. Brainwaves, much like smart phone applications (“apps”), allow us to communicate our thoughts, emotions, and behaviors.

Testing for concussion

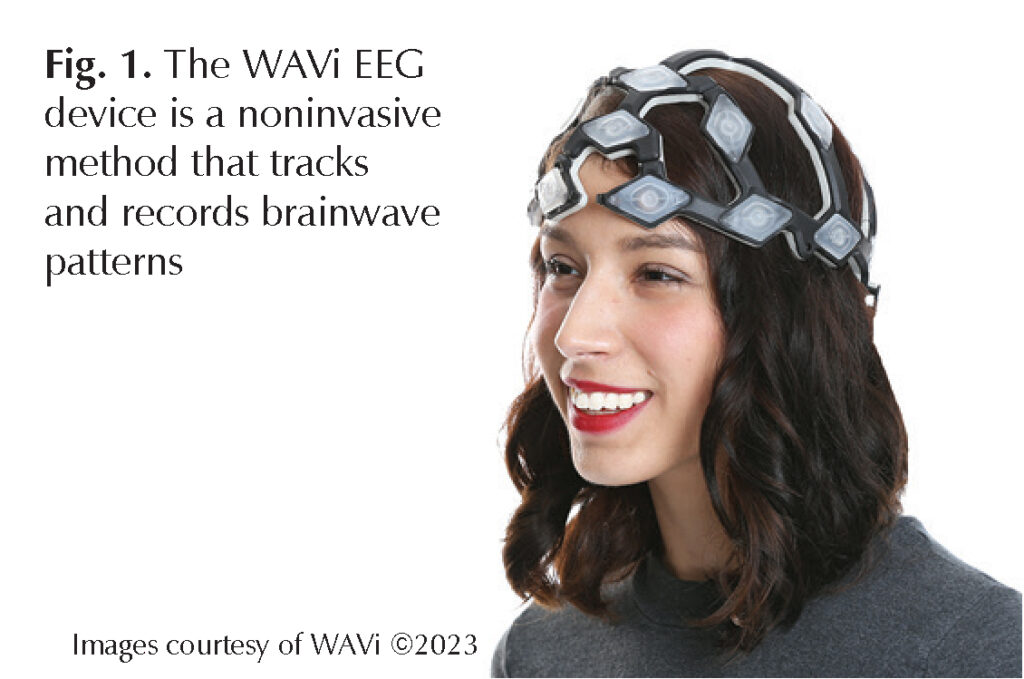

Evoked response electroencephalogram (EEG) testing is a new modality that allows concussion specialists to objectively measure and assess the brain’s network of electrical functions (our brain “apps”) at rest and during mental tasks. Researchers report that the inclusion of evoked EEG with concussion diagnostics can improve accuracies to above 95%. More importantly though, they have also found that evoked EEG’s are a powerful measure of brain recovery that can detect deficits even after symptoms have resolved. Physicians use WAVI, which is a new device that uses the EEG technology, to help them diagnose, treat, and plan the long-term management of concussions.

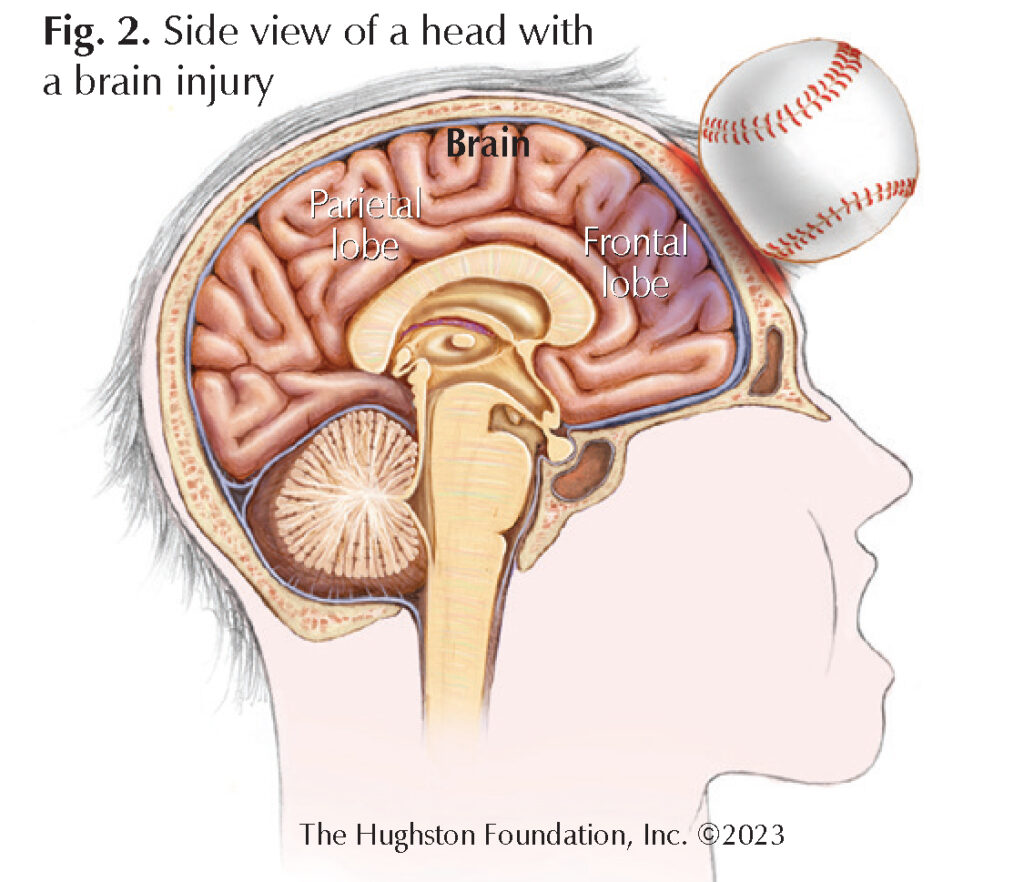

The WAVi EEG device is a noninvasive method that tracks and records brain wave patterns via a number of electrodes during a 20-minute scan (Fig. 1). This device evokes an EEG to see how well the brain is processing. The evoked EEG signal most sensitive to concussion appears as a positive voltage occurring on average 300 milliseconds after the stimulus, and is therefore known as the P300 response. Physicians can see the P300 signal on an EEG as a fast, single electrical spike in response to a sensory, cognitive, or motor stimulus. Researchers believe the P300 signal comes from the parietal lobe, a portion of the brain, which has an important role in decision-making and response to stimulation (Fig. 2). The WAVi device can measure how efficiently the brain is able to use available brain “apps” to complete a given task. For example, the WAVi will look at brain regions “apps” that are not activating consistently and are therefore not functioning well. This information helps the physician determine the direction of rehabilitation efforts, the types of tasks one should be practicing most, and the training approaches to speed recovery.

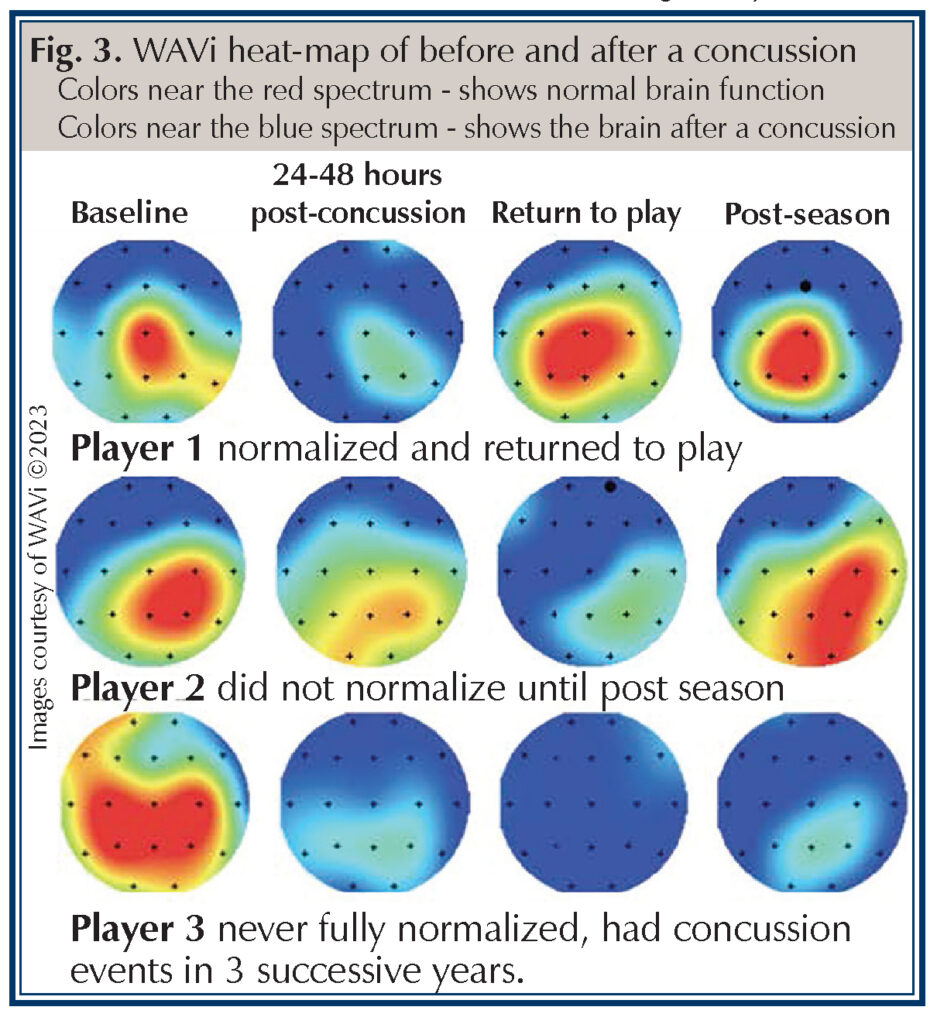

Additionally, the WAVi brain scan allows for a visual representation of the electrical changes in brain neural pathways following a concussion. Depicted is a heat-map visual representation of 3 players: before and after a concussion and at the end of the season (Fig. 3). Colors near the red spectrum reflect higher brain voltages, which shows normal functioning of the brain and colors near the blue spectrum reflect lower brain voltages that show the brain after a concussion. Additionally, this graph shows the significant shift from red spectrum to blue spectrum—see the left column, which is a baseline scan to the second column—after a player sustained a concussion. The pictogram of player 3 indicates the electrophysiology of the brain has not returned to normal following the concussion.

On the forefront of concussion care

Concussions cause measurable changes in the electrophysiological functioning of the brain. As such, concussed participants often pass clinical tests while still displaying electrophysiological deficits in the form of a delayed P300. By using evoked response EEGs and technology such as WAVi, we are on the forefront of concussion care and better able to determine when an athlete has still not recovered enough to safely resume their sport.

Author: Derek A. Woessner, MD, FAAFP | Montgomery, AL

Last edited on December 13, 2023