In the elderly population, the proximal humerus (upper arm bone near the shoulder) ranks third as the most frequent fracture. Our working population is aging; as a result, researchers believe the incidence of proximal humeral fractures will increase, making it important for us to understand more about these potentially life-changing injuries and their treatments.

Symptoms

Symptoms of a humerus fracture can include pain, swelling, bruising, and an inability to move the shoulder joint. You may experience a grinding sensation when you move your shoulder and you may notice some deformity or that your shoulder may not look right.

Unlike many chronic conditions associated with overuse or age, fractures are a result of a specific injury. The most common mechanism is a fall from a standing position. The proximal humerus anatomic structures include the humeral head, the humeral shaft, and the lesser and greater tuberosities (Fig. 1). Radiographs (x-rays) are the first imaging study to characterize these fractures with a computed tomography (CT) scan able to provide additional information if surgical intervention is considered.

Treatment

Several factors can influence treatment, including the patient’s lifestyle, the surgeon’s experience, and, of course, the fracture itself. Often, with complex fractures, the most disconcerting factor is the disruption of the blood supply to the humeral head. This is frequent in cases with displacement and multiple fracture pieces. The greater the risk of blood supply disruption, the more likely the potential need for shoulder replacement.

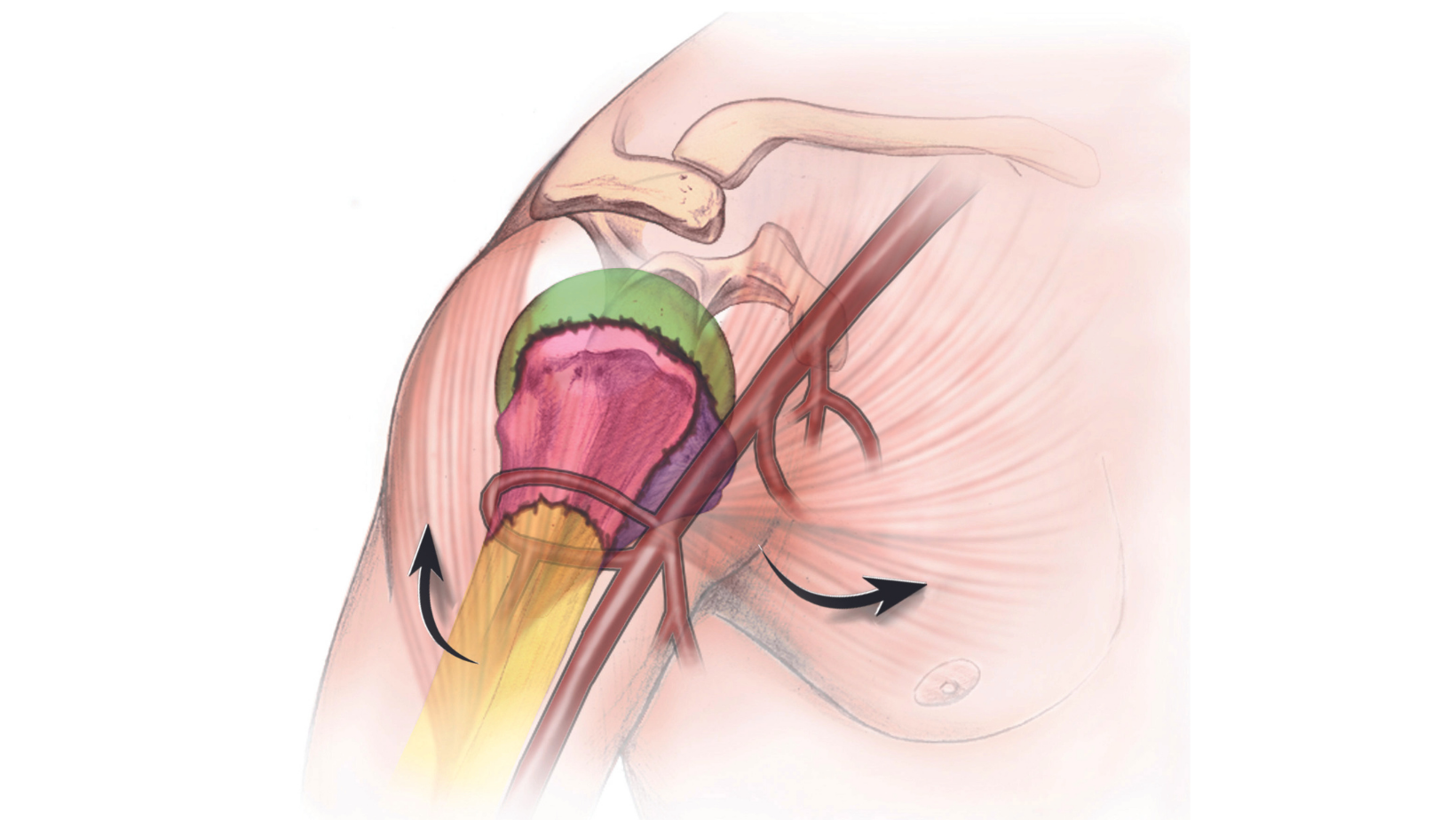

The tendons that attach the muscle to the bone can displace other pieces, as well. For example, the humeral shaft is often rotated and angulated by the pull of the pectoralis major muscle. The greater tuberosity is the location where 3 of the 4 rotator cuff tendons attach (the supraspinatus, infraspinatus, and teres minor) and in unstable fractures this bony piece can migrate away from the shoulder joint as the pull of the cuff is not resisted. The lesser tuberosity is the attachment site for the largest rotator cuff tendon, the subscapularis. Depending on where the fracture occurs, there will be 2, 3, or 4 independent large fracture pieces.

The majority of fractures do not require surgery. Clinicians often prescribe pain medication and sling immobilization with early physical therapy to restore function. With displaced fractures in healthy individuals seeking to maximize shoulder function, a physician may recommend surgery. The most common surgical options include intramedullary nailing—i.e., for 2-part fractures to put the “ice cream scoop back on the cone”—plate and screw fixation—i.e., for 3- and 4-part fractures able to be fixed (Fig. 2)—and replacement, if the blood supply to the humeral head is disrupted or the head is split into more than 1 fragment.

If the decision is to replace the joint, the most common option is a reverse total shoulder as the healing of fractured tuberosities is unpredictable and a reverse procedure does not depend upon rotator cuff function to restore function.

Author: Brent A. Ponce, MD | Columbus, Georgia

Last edited on August 29, 2025