Sport participation after anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction (ACLR) surgery can be quite challenging for anyone; however, it can be especially difficult for young athletes. Short- and long-term effects of an ACL injury can include muscle weakness, poor knee function, and knee osteoarthritis (degenerative joint disease) later in life. Returning to sport after ACLR surgery can also be a grueling and painful process and it puts the athlete at a much higher risk for reinjury. Some researchers have found that as many as one-third of patients who have had ACLR surgery experience a second ACL tear,¹ while others have found successful participation without injury with the right timing and knee function. Getting back in the game should be a progressive and patient-tailored process that helps to decrease the risk of reinjury or injury to the healthy knee. This article aims to outline some of the most important pieces of the puzzle that can help a young athlete return to sport safely and without reinjuring the ligament.

How can we reduce the risk of reinjury?

An athlete’s return to the sports field should entail a multifaceted approach that requires the athlete, physical therapist, athletic trainer, and surgeon to all be on the same page. The criteria for a safe return are, but not limited to, psychological readiness, functional and strength tests, physical readiness, and timing.

Psychological readiness

The athlete’s psychological readiness plays a crucial role in determining when to resume competition. The athlete should feel ready and have confidence in his or her knee function. Fear of reinjury can lead to decreased motivation and activity, which can be related to poorer performances on functional and strength tests.² A progressive patient-tailored rehabilitation program can help the athlete begin to trust their knee stability. The process occurs over time while completing the exercises and experiencing the progress each week.

Functional and strength testing

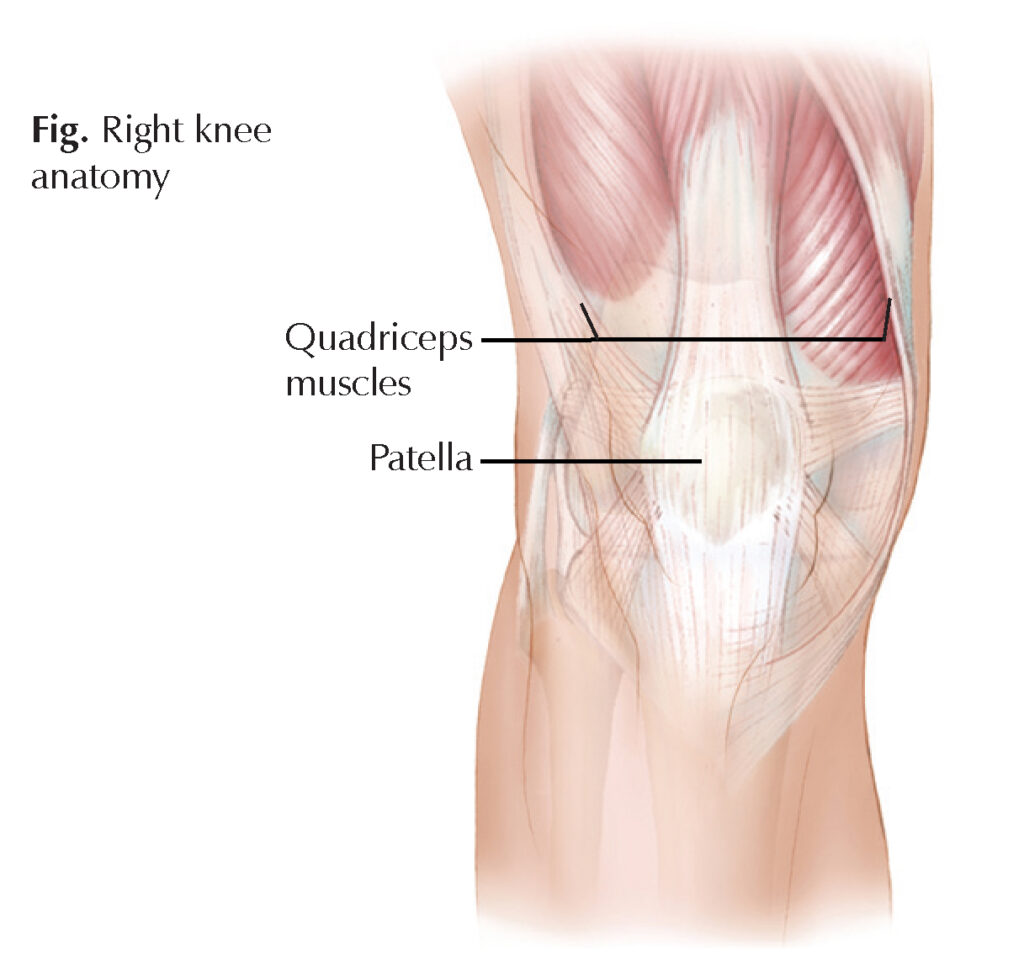

A comprehensive rehabilitation program designed by a physical therapist and directed by the surgeon, and then followed by an athletic trainer, often proves the most successful. Early physical therapy often focuses on exercises that do not place excess stress on the graft. During the first 4 to 6 weeks, the goals are to minimize pain and swelling, restore patellar (kneecap) mobility, restore quadriceps activation, and to normalize motion (Fig.). During the 6 to 12 week phase, the patient will work to develop strength, stability, and endurance. Often symmetrical quadriceps strength and the single-leg hop test, where the athlete hops and lands on the same leg without swinging their arms or needing extra hops after landing, are the cornerstones of the criteria. Depending on when the athlete is ready, more sport specific tests and exercises are performed in the late phase of rehabilitation.³

Readiness of the athlete

Once the athlete is ready to return to sport-specific activities, a gradual increase in training load4 ensures that the athlete is prepared to return to a competitive level. A gradual return to activity is a vital part of the rehabilitation process. The athlete needs exposure to a training stimulus and stress appropriate for their current physical shape, which allows adaptation to take place. Some athletes tend to believe that “more is better,” and, therefore need protecting from their overzealousness. If the training is too strenuous and if the athlete does not recover appropriately, it can lead to increased risk of injury. Different sports present diverse demands on the knee; therefore, sport-specific exercises to improve function and build confidence are necessary. For example, in pivoting sports, such as football or soccer, players who can perform a specific motion prior to returning to sport have a much lower risk of reinjury.

The perfect time

Our bodies need time to heal, so when recovering from ACLR, time is an important part of the treatment plan to reduce the risk of reinjury. Previously, physicians often considered a 6-month mark as an adequate timeframe given the rehabilitation program also proved the athlete ready. However, recent research has found that for young athletes returning to sport before 9 months increases their risk of reinjury by up to 7 times. An additional study found that delaying return decreases risk of injury by 51% for each month before the 9-month mark.3, 5 This does not mean that the athlete can sit on the couch for 9 months and then go set a single-season rushing record in the NFL like Adrian Peterson did. Delaying sport participation up to 9 months can definitely reduce risk of reinjury significantly, but there is a need to complete a gradual, progressive rehabilitation program.

Minimizing the risk

After ACL reconstruction, returning to sport too soon, or being ill prepared can cause devastating consequences. Unfortunately, we cannot eliminate the risk of reinjury completely when getting back into the swing of things; however, with a collaborative, thoughtful effort of the athlete and the treatment team, we can aim to minimize the risk as much as possible.

Author: Malte Krapp, BS | Columbus, Georgia

References

- Filbay SR, Grindem H. Evidence-based recommendations for the management of anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) rupture. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2019 Feb;33(1):33-47. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2019.01.018. Epub 2019 Feb 21. PMID: 31431274; PMCID: PMC6723618.

- Paterno MV, Flynn K, Thomas S, Schmitt LC. Self-Reported Fear Predicts Functional Performance and Second ACL Injury After ACL Reconstruction and Return to Sport: A Pilot Study. Sports Health. 2018 May/Jun;10(3):228-233. doi: 10.1177/1941738117745806. Epub 2017 Dec 22. PMID: 29272209; PMCID: PMC5958451.

- Grindem H, Snyder-Mackler L, Moksnes H, Engebretsen L, Risberg MA. Simple decision rules can reduce reinjury risk by 84% after ACL reconstruction: the Delaware-Oslo ACL cohort study. Br J Sports Med. 2016 Jul;50(13):804-8. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2016-096031. Epub 2016 May 9. PMID: 27162233; PMCID: PMC4912389.

- Blanch P, Gabbett TJ. Has the athlete trained enough to return to play safely? The acute: chronic workload ratio permits clinicians to quantify a player’s risk of subsequent injury. Br J Sports Med. 2016 Apr;50(8):471-5. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2015-095445. Epub 2015 Dec 23. Erratum in: Br J Sports Med. 2019 Sep;53(18):e6. PMID: 26701923.

- Beischer S, Gustavsson L, Senorski EH, Karlsson J, Thomeé C, Samuelsson K, Thomeé R. Young Athletes Who Return to Sport Before 9 Months After Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction Have a Rate of New Injury 7 Times That of Those Who Delay Return. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2020 Feb;50(2):83-90. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2020.9071. Erratum in: J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2020 Jul;50(7):411. PMID: 32005095.

Last edited on May 11, 2022